Without The Box Thinking

To do what no one has done before, you must by definition think as no one has done before. So, you must learn to think without the box.

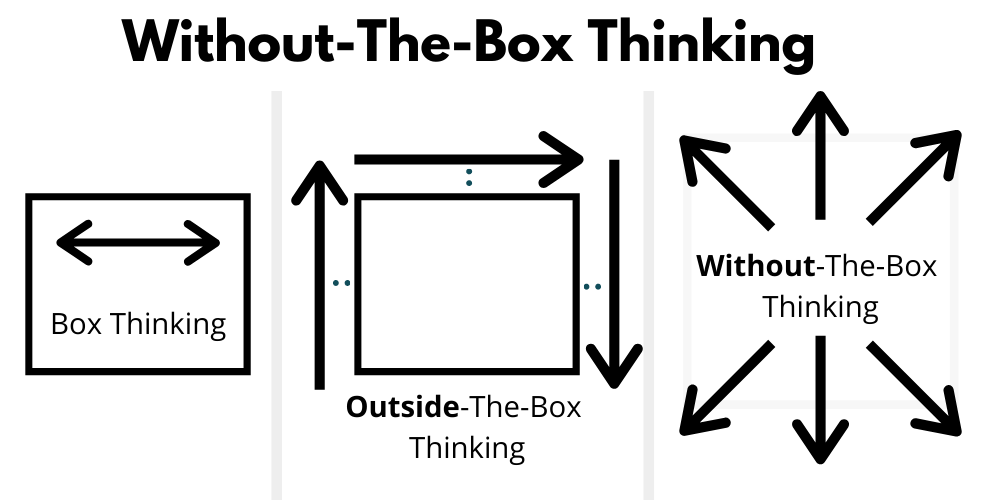

Everyone encourages you to ‘think outside the box’, as the famous saying goes. The only issue I have with Outside-The-Box Thinking is that this thinking still relies on ‘the Box’. It still relies on assumptions, assumptions tethered to the way things have always been.

The Three Levels of Thinking

I prefer a different style of thinking; Without-The-Box. This involves asking

- Why is the box there to begin with?

- Who put it there, and why?

- Should it remain there?

Welcome to Without-The-Box Thinking.

Today I’m going to introduce you to Without-The-Box Thinking. Whilst we can’t hope to master what is in truth a life-long skill and pursuit, today we can certainly begin the journey. To do this, we will

- Clarify why Without-The-Box Thinking is important

- Show the dangers of rigid thinking

- Give some examples of Without-The-Box Thinking

Famous Without-The-Box Examples

No one thought making a rocket company that could rival NASA, or a car that was electric, affordable, classy and fast were possible. Luckily Elon Musk listened to his intuition and his mission more than the people who didn’t understand his objectives.

Charles T. Munger and Warren Buffet… heard of them? Champions of a multidisciplinary approach which they’ve used to realise a lot of success in investing and in life. No school has ever taught that a sound understanding of psychology, physics AND economics would create an edge in public markets, or life.

Luckily they had the guts and intuition to do what no one had done before.

These sorts of stories are the very essence of a good Hollywood film; Check out The Big Short and the Michael Burry story. He’s credited as being the first person to recognise the subprime mortgage crisis, but everyone thought he was crazy – “No one shorts the housing market!”

What about Moneyball (2011) and the Billy Beane story? All the weathered scouts turned up their noses when he ignored them to follow the analysis of a twenty-seven year old who is applying economic principles to baseball. Look how that turned out.

Just think about the first person who ever conceived of an aeroplane, of electricity, or the personal computer.

These changes were so radical that they often attracted ridicule and resistance, despite appearing completely logical through the frame of hindsight.

People veer toward comfort, settle into boxes of thinking that provide that comfort, and have trouble dealing with ideas that break through those boxes.

But where would we be without those who had the courage to see things without our base assumptions?

Three Examples of ‘Boxes’.

Box One: Education

Education is a big topic – Mainstream education today takes a strange batch-based approach, almost like the McDonald’s model for fast food. This system treats everyone the same and teaches them the same things, even though everyone 1) learns differently, 2) learns at different paces, 3) contributes differently in the outside world and 4) values different things.

Because of this, the majority of what we learn at school is what I would call FYI. FYI is ‘For-Your-Information’, in other words, you may not want or need to know but I’m going to tell you anyway.

How often have you used Shakespeare and trigonometry since you left school?

Modern schooling and university seem to operate as though every day were opposite day.

Instead of stimulating the many, they stimulate only the few.

Instead of fostering our independence and maturity they tell us when to sit, when to stand, when to come and when to go, when to eat and when to shit.

Instead of encouraging energy and divergent thinking, we punish and even pathologize the early embers of entrepreneurial traits.

Instead of helping us develop a sense of our interests, they attempt to force interests onto us.

Instead of unlocking our creativity, the skill most vital in our society, the strict regime of obedience and linearity kills creativity.

Instead of without-the-box thinking, the system breeds box-thinking… safe and unspectacular thoughts which lack imagination and perspective.

I would go as far as to point to this as the mummification of society, enhancing our fear of failure and our unwillingness to try.

Sarah Blakely says it best:

“I started to cry… I had just spent 16 years of my life in school being taught what to think, but nobody had ever taught me how to think.”

Why? Why do we get education so wrong? Well, first we ask,

1) Why is the box there to begin with?

The modern education system was introduced around the time of the Industrial Revolution. This was a time when we shifted from rural and agricultural communities to big dehumanising urban environments, which centred around manufacturing.

This answers the second question around who put the box there, and why? – Manufacturers needed people to behave like cogs in a machine on the production line. It’s quite a dehumanising way of treating the lower classes, and we’re still feeling the dehumanising effects of the Industrial Revolution today.

It doesn’t help that we maintain the systems that were designed to meet it’s dehumanising purposes. So, you can answer question three yourselves:

Should the box still be there?

For anyone who knows our work at Doohat Labs, you’ll see my personal passion for this issue, as well as my bias, which I feel I must acknowledge.

But if I can offer a personal opinion at this point, it would be that our current response to the education problem is ‘Thinking Outside the Box’.

What do I mean by this?

We introduce incremental reforms with subtle changes to classrooms and curriculum. But to quote Sir Ken Robinson, when it comes to education “reform is not enough”.

Too much of our efforts revolve around using the same core construct that is flawed. If the hammer is broken, the solution is not a different nail.

We add programs and initiatives to these flawed systems, which is what I call the attempt to ‘think outside the box’ – which is still relying on the box.

Thinking without the box is more radical and goes further by asking questions without-limits, and thinking as if anything were possible.

For example:

Are we better off removing the current schooling system altogether?

Would we be better off with more at-home education, or a more minimalist approach to school curriculum (for example, just basic reading, writing and counting)?

Is the classroom a good environment to deliver education?

Should we introduce initiatives that work alongside schooling, to fill the gaps?

Could school be replaced with something far less structured and dogmatic, and be more about play and creativity?

Box Two: Charity

According to OECD DAC statistics, since aid began in the 1960s donors have given a grand total of US$502 billion to sub-Saharan Africa, which is worth about US$866 billion in today’s prices.

Incredible resources have been put into aid and charity, over a long period of time, and this continues to this day.

So why are there still ‘poor’ and suffering people all over the world?

Applying the Without-The-Box Thinking techniques might help us gain some clarity in this much needed area, because many of our techniques for helping others have proved fruitless over time. In many cases, they’ve made things worse.

Why is the box there to begin with?

There’s a fascinating, seminal TED Talk by Dan Palotta titled The Way We Think About Charity Is Dead Wrong.

In this TED Talk, Pallotta suggests that the Western version of charitable giving has its origins in the early American settlers, who emigrated from Britain to have more freedom over religious expression.

But this early settler community had a problem; they were wealthy. And wealth is associated with guilt in many religions, especially Christianity (recall, Jesus Christ told the wealthy man that to enter the Kingdom of Heaven he had to divest himself of all his riches).

And so, the strategy of relieving this guilt was to donate their excess wealth to the ‘needy’.

But the texts of dominant world religions like Christianity were developed in a radically different context, before the revolution of credit that turned wealth from a zero-sum game to a positive-sum game.

In other words, the story of the wealthy man in the Bible makes sense because at this time, the perception was that one was only rich at the expense of someone else- but this is no longer considered a reality.

Charitable giving was primarily designed around relieving guilt. This is not always the same as helping people, as I learnt during my time working with From the Ground Up in Nepal.

Our default solution to most problems is to hand over a cheque, but this is rarely effective. The analogy I like to use is giving flour to someone who doesn’t know how to bake, and expecting them to be fed for life.

There is no point giving someone a single ingredient and telling them to bake. And how useful is a tool that they’ve no experience with, that they don’t know how to use? Aid on a macro level, and microfinance on a micro level, risk exacerbating the situations of the ‘needy’ by adding crippling debt to their list of woes.

This leaves the situation worse than it even was before. To quote Munger;

If you want to help India, the question you should consider asking is not: “How can I help India?” instead, you should ask: “How can I hurt India?” You findwhat will do the worst damage, and then try to avoid it.

On changing lives

The way to change lives is not necessarily that capital-intensive. From my limited but insightful experience and research, it tends to involve empowering people by listening to them intently, and then giving them the skills they need, all whilst creating ripple-effect solutions.

So slowly reforming our aid and charitable systems (thinking outside the box) is unlikely to yield meaningful results when the core purpose of these systems is to relieve guilt for donors and volunteers, rather than assist the ‘needy’.

I recommend you look into Interlock Construction, as well as the work of Ernesto Sirolli as Without-The-Box solutions to the problems of how to create positive and sustainable impact.

Neither has required donations, neither has tried to put a band-aid on a broken arm. Each has used the principles of listening, empowerment and regular good-old for-profit business as solutions to positive and sustainable impact.

Box Three: Real Estate Commission

The third and final example I’ll talk through today is less significant, but refers to an industry I got to know well through Sydney Listings and launching the $9,999 experiment in 2019.

Hopefully it provides a different perspective to the other two social criticisms.

In Australia, real estate agents charge on average around 2% of the final sales price to sell a home. In the USA, the system is quite different and it naturally ranges in other parts of the world.

But where did this pricing structure come from? Real estate used to rely a lot more on local offices in each suburb. If you wanted to buy in a particular suburb, you could check out the windows of these offices to see the properties they’d listed on the market.

The commission model was based on property prices at this time. Then, the internet came along and introduced listing portals; now, instead of driving around and checking out a range of offices, people could simply look at one or two websites to check out a property.

Yet a lot of the vestigial elements of real estate have stuck around – it takes time for change to be implemented in any industry. But more and more we now see new business models implemented by real estate agencies that take advantage of the new economics like Purple Bricks.

A lot of the functionality can be centralised. Instead of ten offices in a region with ten teams of onshore admin staff and ten rents and ten times the overheads, these can be consolidated into one office. Check out the animated video for a clearer explanation.

A note on ants

E.O. Wilson did a study on ants. Ants were found to carry a dead ant out of the hive, but Wilson found that by painting the pheromones of a dead ant onto a live one, the other ants still carried it out of the hive, despite its kicking out and resistance!

The other thing about ants is that they often follow the ant in front of them. So when ants get into a circular pattern, they will often continue to follow each other around till they die… talk about the blind leading the blind!

These are the consequences of excessive box-thinking: Simply inheriting ideas without questioning and challenging them, at the extreme end, is the very spark of wars and genocide.

The more you look into human psychology the more you see our vulnerability to excessive box-thinking, and thus our need to think more proactively.

The outside-the-box thinking in real estate will be to make small changes like more creative postal advertising or a more appealing website.

But the person who can think without-the-box and challenge the core assumptions, has the capacity to change the construct altogether and enter a category of one, rather than a category of competition with the rest.

Einstein and First Principles Reasoning

Albert Einstein is credited with achieving what he did because of his emphasis on using First Principles Reasoning. This idea in physics is stripping back all assumptions to the most fundamental, and then reconstructing theory from there.

As time goes on, technology, innovation and cultural changes shift paradigms and create new possibilities and efficiencies. We often miss these because, like the ants, we are so loyal to our previous programming.

Greats like Einstein seem to have this ability to question what everyone else takes for granted. They ask questions that start with ‘Why do we always…’ or ‘Do we really need to…’, and these questions lead to interesting places.

I find it useful to every-so-often destroy my assumptions and visualise what could be done if there were no limits… it is easier to pear these back to ‘reality’ than never flirt with them at all.

Assume almost nothing. There are boxes everywhere that I haven’t dared explore yet today. Be bold in your questioning.

Why do we form relationships? Why do we get married? Why do we prioritise economic growth? Why do we have politicians? Why do we have money? Why do we have police? Why do we have jobs? Why do we have religions? Why do we have atheists? Why do we live in houses? Why should we work hard?

Remember the questions:

- Why are these boxes there to begin with?

- Who put them there, and why?

- Should they remain there?

This is nothing more than an introduction to Without-The-Box Thinking; as I said, this pursuit is not one I claim to have mastered, but I do see it as a worthwhile life-long pursuit, to every so often question The Matrix around us.

To do what no one has done before, you must by definition think as no one has done before. So, you must learn to think without the box.

If you like this concept, part two is here >> How to think through boxes.

Who do you think of when you read this? Would this piece ‘open a door’ for someone you know? Why wouldn’t you share it with them?

Remember, the best way to open a thousand doors for you is to open doors for others.