The Expectations Gap

I left high school thinking I would become one of the greatest film directors of all time. I pictured myself winning an Academy Award for Best Original Screenplay, Best Director and Best Actor in a Lead Role all in one fell swoop before the age of thirty.

To me, that was the way to go down as the greatest and stand out from everyone else who’d ever worked in film: To do what no one else has done, all before the age of thirty. As such, achieving all this before thirty became an ESSENTIAL, a REQUIREMENT.

Failing to live up to this would be a huge and bitter disappointment.

Note, a full four podcast episodes are dedicated to the Expectations Gap (and Expectations Trap)

For Youtube Versions Check Out: #029 Optimism Bias, #030 The Height Analogy, #031 Navigating Achievements and #032 The Expectations Trap

Audio Only Episodes are here or wherever you get your podcasts.

Fast forward to the present day

At the moment I’m twenty-five years old, sitting in a Sydney cafe at 7:05am writing this post. I’m a long way from Hollywood – around 12,066km in fact, and even further away from winning an Academy Award for anything.

It is perfectly fine to dream big – if anything, I dream even bigger these days. But this dream I refer to from my past soon evolved into something else entirely.

An Expectation

Last time out we talked about The Happiness Curve – how the relationship between time and happiness follows a U-shaped distribution – it starts high in childhood, and self-reported happiness falls to a trough in midlife before then turning and increasing over the remainder of life.

This blog piece follows directly on from The Happiness Curve, and offers the theory that best explains the curve; this unexpected finding that older people tend to get happier, not more miserable.

The Expectations Gap

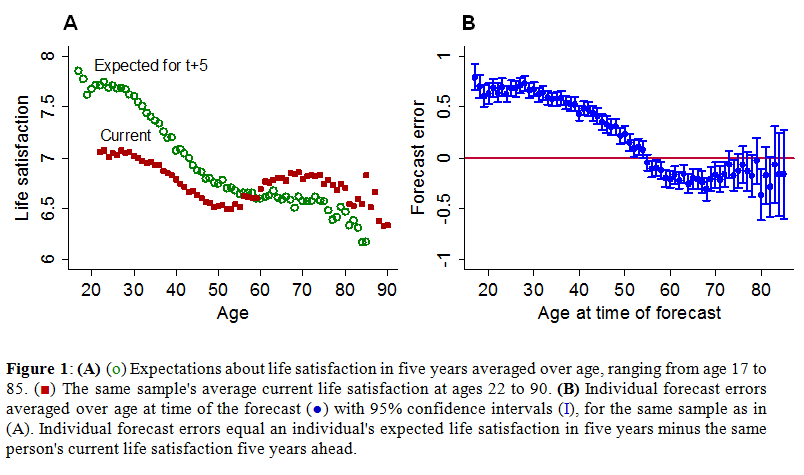

The below graph is from a publicaton by Hannes Schwandt titled ‘Unmet Expectations as an Explanation for the Age U-Shape in Wellbeing’.

Pay particular attention to the graph on the left, and the green and red lines. What this study recorded was the expectations people had for their happiness or wellbeing level in five years’ time, and compared that to current life satisfaction. The finding was that young people expected to be much happier in future than they were at the time of measurement.

Pay particular attention to the graph on the left, and the green and red lines. What this study recorded was the expectations people had for their happiness or wellbeing level in five years’ time, and compared that to current life satisfaction. The finding was that young people expected to be much happier in future than they were at the time of measurement.

Older people however, had lower expectations of future happiness than they actually experienced at time of measurement – a complete inversion.

But at what point did this switch over? Well, if you read the article on the Happiness Curve, you might guess.

Midlife.

So what is going on?

It appears that in youth we have an optimism bias. We have higher expectations of the future and specifically, our future achievements – you have seen already my very comical personal example, and the unrealistic expectation that I would make history. Yet, this expectation was based on insecurity – it was a goal that was composed completely of extrinsic, external factors – an award given power only by others.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VzFngT50jkE

Up until midlife, most people have a tendency for aspiration. We compare ourselves to our peers and look for a yardstick by which to assess our achievements. For example, when I was younger I was only looking at other friends to judge how I was doing with life.

Were they having more success in their romantic relationships? Were they fast-tracking their careers? Were they getting paid more?

In the past, comparison to others made sense for survival

If your neighbour grew twice the amount of crops you did, or hunted more successfully, it made sense, for survival purposes, to observe them and figure out what you were doing wrong.

Times have changed – environment and culture have come a long, long way. In the modern world we’re far better served turning up the volume on our intrinsic, internal metrics. In other words, it matters far less what the expectations and achievements of others are in relation to our own.

I so often felt insecure when I was younger because I was not doing well in comparison to most people in any of these areas (supposedly). But the problem was not the gap between my progress and theirs, the problem was, I inherited expectations from others that did not serve me.

The Height Analogy

If I woke up tomorrow and grew thirty centimetres, or one foot, I’d be delighted. If however, all my friends had grown sixty centimetres or two feet, then I’ll actually be unhappy even though my personal progress were the same.

If people I don’t know on the other side of the world grow less or more, it does not impact my satisfaction – they are not part of my comparison sample. I compare myself to those I can observe. More specifically, the most significant comparisons I make are to those I spend the most time with and find most similarity with. This is how we are wired as people (See Astro the Dog).

But really, there is no such thing as a true peer or true comparison. Not even my best or closest friends are ME. Logically and unemotionally, there is no reason to anchor my satisfaction to their progress in any metric, particularly their professional achievements and income levels.

Implications from the Pleasure Treadmill

What most people do not appreciate is that achievement, the outcome we so often crave and put on a pedestal, is a trap for two reasons. It tends to be extrinsic, and it tends to be a pleasure experience, not a fulfillment exercise.

I discuss this in the blog piece on The Pleasure Treadmill: achievements are much more like the experience of attending a rock concert, taking a drug, or having casual sex. They are enjoyable for a brief moment – an orgasm if you will – then the pleasure fades and we return to equilibrium.

Fulfillment, unlike pleasure, is lasting and durable. Fulfillment comes from loving your journey, having interests, relationships and communities that you engage in long-term… the reward from these experiences is ongoing and continual.

Be wary of achievements

There are several prominent examples I can draw from current popular culture. The first is a prolific song by Mike Pozner called I Took a Pill in Ibiza. This song is about his experience of the fall that came after a smash hit song catapulted him to stardom – a fall that no one prepared him for.

“You don’t ever wanna step off that roller-coaster and be all alone”

This is the same experience I casually refer to as ‘Post-Olympic Depression’ – the well documented yet rarely discussed down Olympians experience after they win gold and return home. Olympians spend years and years working towards a single moment – but the high and glow from that moment is still only fleeting.

But so often, they were expecting it to last longer, to endure… there lies an Expectations Gap.

Think again of the example of the Academy Awards I craved growing up. The expectation is not that these awards would make me happy for just two weeks! But that this achievement would give me fulfillment for the rest of my life!

But an Academy Award, or any extrinsic reward for that matter, is incapable of doing this.

So, what do you do when that reality sets in? When you feel your lowest at the time you’re expecting to feel your best?

Now ask a second more foreboding question. How many of our social problems and unexplained suicides can be attributed to this expectations gap?

I felt this first hand.

I struggled through adolescence and early adult life with this very problem. On the outside I was confident, intelligent, healthy and in good shape, widely loved and achieving. Yet at times, on the inside, I couldn’t understand why I felt so unhappy.

I expected to be happy, but was often the furthest thing from it. My theory at the time was that I was just messed up, I was an outlier, someone who didn’t belong. There was something wrong with my programming, and there was no point talking about it because no one would understand.

The Expectations TRAP

This is a long-winded way of discussing the following:

Firstly, we are unlikely to be fulfilled when our expectations (separate to our ‘dreams’) are judged against the ‘progress’ of others. (It’s also worth noting the Iceberg Effect, and that the achievers might not even be fulfilled.)

Secondly, even if we do ‘achieve’ – these achievements that are based on extrinsically defined rewards, that resemble gold medal moments and Academy Awards – we still will not have enough to provide ongoing fulfillment.

Sometimes, this can be even worse! Because there is a larger gap between the expected wellbeing and the actual disappointment. This is why we have oversimplified cliches like “rich people are not happy”. Money and income levels can provide sporadic pleasure and signal achievement, but they cannot easily sustain a sense of fulfillment on their own.

There is no upside to holding high expectations on extrinsic achievements. \

Consolidating the midlife crisis experience

As is so beautifully portrayed by Jonathan Rauch in The Happiness Curve: Why Life Gets Better After Midlife, midlife is so often the junction after which we shift from aspiration to appreciation.

We start to realise that achievements and the extrinsic rewards we chase will not fulfill us – as a result we start to align our expectations with reality. We start to realise we will not reach certain career peaks we’d held out for, and often sense that we’ve overlooked greater value in more accessible places.

In general midlife is a period where we shift to a mode of appreciation. Appreciation is a simpler and more effective strategy by which to reveal a good life to oneself.

Infinitely So!

People don’t start achieving more in midlife (on average) – this cannot happen to everyone globally and so it could not explain the Happiness Curve. What does happen is this shift in expectations, once the world teaches us how unrealistic and useless these expectations are.

We are not barred from great achievements but we understand that these achievements are limited in the value they provide.

Older people are much slower at scrolling social media.

Younger people are in a rush. They scroll social media faster, which reflects their mode of life – they are in a rush to go places and achieve, trying to consume as much as possible.

Ironically it is the older and wiser amongst us who take much more time when they scroll social media. This is ironic because they are the people with the least time left to live. But what are they scrolling? They’ll probably be looking for photos of their grandchildren that they can pause, digest holistically and appreciate.

My grandmother leads a simple life – she prays daily, stays mainly at home and receives joy exclusively from seeing friends and family, in particular children and grandchildren. She has been a widow since 1995, and though I haven’t measured her self-reported wellbeing, the lesson resonates.

Low Expecations. Big Dreams.

Coming up next we will talk about strategies for protecting against this expectations gap:

See ACCELERATING MIDLIFE CRISIS here

Note, a full four podcast episodes are dedicated to the Expectations Gap (and Expectations Trap)

For Youtube Versions Check Out: #029 Optimism Bias, #030 The Height Analogy, #031 Navigating Achievements and #032 The Expectations Trap

Audio Only Episodes are here or wherever you get your podcasts.

Who do you think of when you read this piece? Would this ‘open a door’ for someone?

If yes, then please remember to share it with them. The best way to open a thousand doors for yourself is to open doors for others.

Michael Gill

Thanks again Joey. My experience is that as we grow ( older), we learn better to live in the present. Reason might be that looking too far ahead might be a waste of time. We should have come to understand the stupid futility of comparing ourselves with others. And, perhaps most importantly and with one exception, we are better able to leave our fears behind. The exception for some is the fear of death and its process. I believe these are some of the most important of life’s lessons and they can take a lifetime to learn. And never forget: each of us is unique