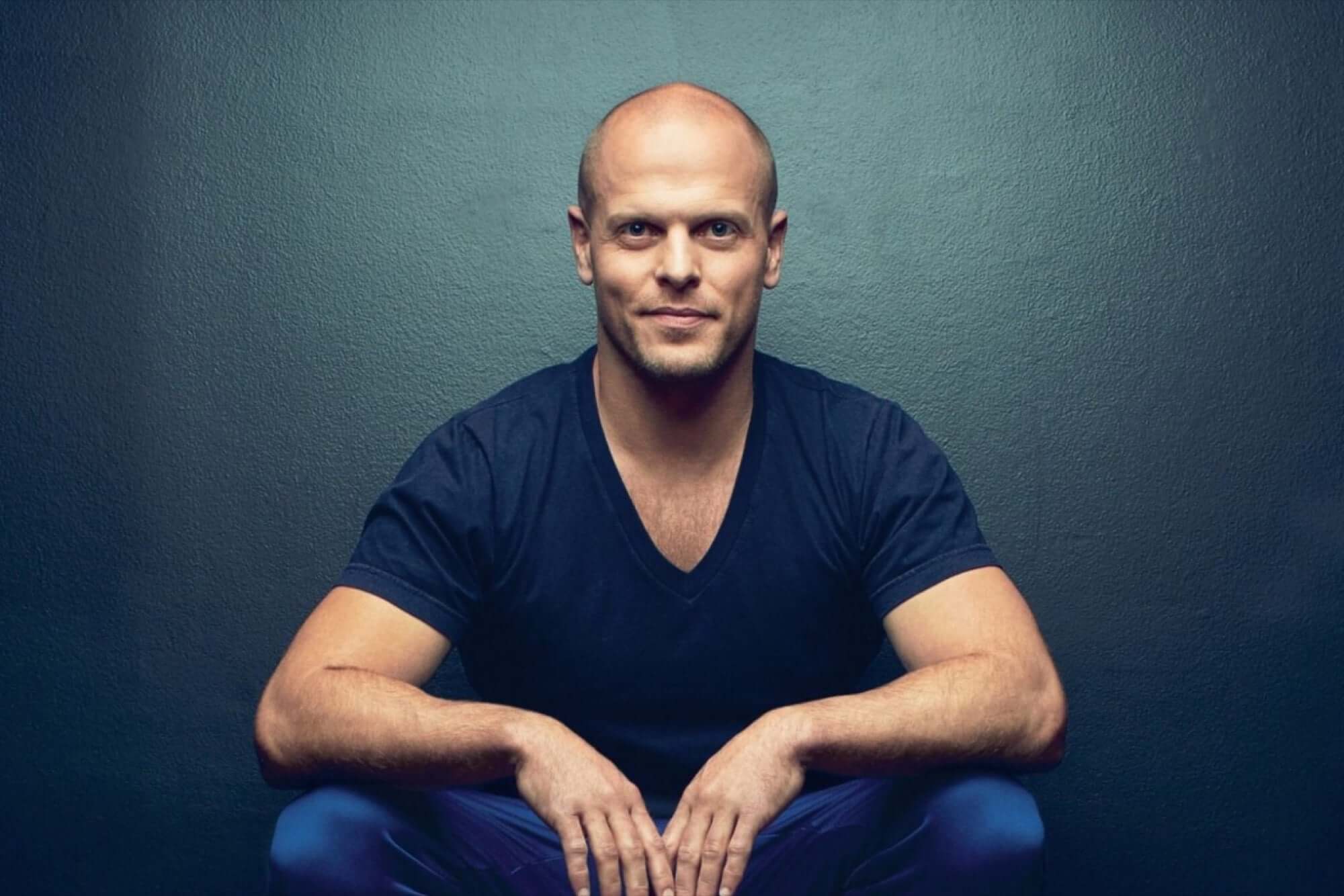

Tim Ferriss on Learning, Early Career and Life Advice

Tim Ferriss is hard to put in one bucket. He is well known in business circles, and is a go-to for things as diverse as lifestyle design, self-experimentation, high performance, health and… well, much, much more.

He’s the author of top selling books like Tools of Titans, The 4 Hour Work Week, The 4 Hour Chef and The 4 Hour Body. He’s most active currently with his famous podcast, The Tim Ferriss Show which is wide-ranging but centred around high performance. On the show he’s unpacked some of the world’s most noteworthy entrepreneurs, leaders, athletes and performers.

So it’s no surprise he has some pretty sage career and life advice to share — he’s invested in companies, written books, started business, dominated the podcasting scene, but also explored practical philosophy, learnt the need to find greater balance in life, pursue meaningful things, and explored health and psychedelics as a means to overcome his own personal trauma from childhood and episodes of manic depression.

Following on from Nassim Taleb, Peter Thiel, Alan Watts and Naval Ravikant, our next modern thought leader to unpack on the With Joe Wehbe Podcast is one of my earliest entrepreneurial role models — Tim Ferriss.

First we’ll unpack his thoughts on learning

Let’s start with Ferriss’ thoughts and lessons on learning itself. Ferriss is a true multi-potentialite — I can’t list all the topics and themes he’s traversed, and I think that’s because when you’re good at self-directed learning, you end up finding the ability to pick up and learn things quickly.

As we’ll unpack in the 4 Hour Work Week, Tim is all about being effective rather than productive. It’s crazy how little of this power people unpack in their lives, often wasting time and taking large detours towards very narrow goals.

So let’s unpack some of the ideas that give him an edge in learning.

Accelerated Learning

Check out episode #228 of the With Joe Wehbe Podcast for the corresponding audio.

Ferriss has four steps to his accelerated learning model.

- Raise the stakes — facing jujitsu pros in the ring raises the stakes instead of practicing quietly away from the big arena. Competing with poker pros and staking his own money and playing in front of a packed audience raises the stakes more than doing research or playing smaller games.

- Use fear as fuel — learnt tips from a surf pro and realised that fear often tells us what we shouldn’t do, but also tells us exactly what we should do. We might also go into fear setting.

- Focus on the 20% of actions that will drive 80% results — “when trying his hand at Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu, Tim didn’t try to learn and master every single technique in the book. Rather, he intently focused on the guillotine choke, one of the most effective moves in the sport.”

- Chunk things down — “When he learned Tagalog, an Austronesian language spoken in the Philippines, Tim found ways to not get overwhelmed by the vastness of a language, its idiosyncrasies, grammar, and vocabulary. He came up with a list of his “deconstruction dozen”: a list of about 12 basic sentences that make up the foundation of any language, its various tenses, and structure.” There’s also a good example in the 4 Hour Work Week of finding loopholes in a tournament, for kickboxing or wrestling I believe it was.

It’s never too late to learn and become good at something new. You have no excuses to not get outside of your comfort zone more often, and pick up new skills thanks to these simple ideas!

Just-in-time learning

Check out episode #229 of the With Joe Wehbe Podcast on this.

This is a very big point, one I’m very passionate about, that shoots in the heart our inefficient multi-decade education system. There is a failure to grasp how people really absorb information.

“I used to have the habit of reading a book or site to prepare for an event weeks or months in the future, and I would then need to reread the same material when the deadline for action was closer. This is stupid and redundant. Follow your to-do short list and fill in the information gaps as you go. Focus on what digerati Kathy Sierra calls ‘just-in-time’ information instead of ‘just-in-case’ information.” — Tim Ferriss in The 4 Hour Work Week.

I spent three years studying psychology at university, and thirteen years at primary and secondary school. Most of that time was spent being given information rather than developing skills — how much of that information have I retained? How much of it do I use now?

Maybe it was ‘good to know’, but I can’t tell you how much of it I have retained. Take the subject of history as an example — at times it was interesting, at others it was boring. History is quite useful but I struggle to recall dates and details of battles. What we memorise for tests is quickly forgotten once we no longer need to worry about the test.

As Alan Watts warned, so much of education has become ‘cultivating a studied mediocrity’, where the point of an education is shallow — to signal to others that you are intelligent. Great if you want status, but not for taking real action. As Ferriss points out — you haven’t learnt anything when you’re memorising information.

Example — website building

Information, facts and figures are only relevant at the time you’re implementing them, so that’s when you should learn them. I don’t need to be a web developer, and I don’t need to remember the skills, that’s too inefficient for me when it’s not my core profession. But now that I’m doing the third version of the Constant Student website, I go back to Webflow University and refresh on how to use their platform — they’ve stored the information for me so my brain doesn’t have to.

If I learnt it a year ago and didn’t use it, I’d just lose it. The other point is that learning how to use tools is great for giving you a sense of possibility and what you can build, but this doesn’t apply to what most people ‘learn’.

As Naval Ravikant pointed out, so much of what we call education and learning is really just crude memorisation without deep understanding. My Dad loved his physics teacher for saying ‘here are the formulas for physics, don’t ask why they work, just remember them’. Great for passing tests, but not for understanding things from first principles.

To catch these episodes on Youtube, head to the With Joe Wehbe Channel.

Takeaways

Be disciplined — learn things because you are naturally curious and excited by them, or because you’re literally about to use the information. Things that are just ‘good to know’ but won’t be implemented can be attractive but your chances of retention are low.

I place more emphasis on archiving than reading. People send me articles, tech tools, Youtube videos, and I think that it will be good to call upon this with ease in the future… I don’t really need it now though. So I use Notion to archive things — I also monetise that because in Constant Student we have the Treasure Chest which is built on the back of my own archiving system of amazing resources.

Okay next I want to get into quality career advice from Tim Ferriss.

Should you be a specialist or a generalist?

This corresponds to episode #230 on the With Joe Wehbe Podcast.

Here he’s referencing Scott Adams — the point is that you need to be in the top 0.001% of a niche or field to really dominate and ‘make it big’. The first question of course, is why do you need to make it big? However I think Ferriss is addressing the concept that, if you have dominance in an area, you get to attract things to you, versus continually chasing them. It can make life more effortless.

Whether you’re a basketball player or lawyer, the major rewards come from being really, really dominant. Not being in the top 20%. That’s the case for the specialist, who is super narrow and all-in on one thing.

The opposite is being a ‘generalist’ — across many different things. This can be more fun, and it comes naturally to us. If you’re too general, no one goes to you for anything and you probably can’t crush a category (assuming that this meets your ambitions for some reason — e.g. being to attract customers or work opportunities on autopilot).

Instead you can be a specialised generalist. What’s that?

This is where you combine two skills that are valuable but are rarely seen together — but are more valuable together. Ferriss gives the example of having a computer science degree and a law degree, or fine understanding of mathematics and public speaking.

You’re not trying to master a thousand different things, but a short list that actually elevate you in a crowded field like law, computer science, math or something else.

Real World Examples I want to highlight

- Jordan Peterson is more than a psychologist. He is philosophical, which goes well with psychology. In addition he’s a captivating thinker, speaker and leader. The combination of these things is what makes him so widely popular and powerful.

- Neil DeGrasse Tyson is more than a scientist. He is charismatic and a great personality, more relatable than say Stephen Hawking. He bucks the introverted scientist stereotype.

- Warren Buffett’s best investment, he says, was in Dale Carnegie’s speaking course… even though he’s famous for investing in companies. Speaking has given him career advantages, confidence and negotiation skills that no doubt aided his financial successes.

I also have a lot of examples from my previous industry of experience in real estate — one of my good friends, Viktor Desovski, created a point of difference because he was first a director at real estate companies before becoming a mortgage broker. This gave him a view of both sides of the fence that few other mortgage brokers have.

Andy, one of the salesmen I used to work with was not only a good agent but was really into digital marketing — this was rare for an agent, yet it goes well with being an agent because we need to market properties! This gave him an edge.

Three simple add-ons from Ferriss to be a Specialised Generalist

The classic example is the speaker — for anything you do, it’s better if you’re able to speak (and write!).

Tim Ferriss recommends these three add-ons that will be relevant no matter your interests or current field. They are speaking, writing and negotiating.

I recently wrote that 90% of my day is writing and speaking — emails, text messages, reflections on vision and direction, social media posts, negotiations, conversations, sales conversations… you name it. It’s hard to go wrong with these foundational skills. It’s actually something we’ve put in Constant Student’s Exponential Career Challenge.

In the Exponential Careers we unpack:

- Time Management

- Networking

- Wealth

- Sales Skills

- Speaking

- Writing

- Leadership

These act like gateway skills… by that I mean, these skills help you open a whole stack of Doors. For example, networking skills might help you get a job offer before it gets advertised online, your speaking skills might help you through the interview, and now that you have the role, you might get offered internal opportunities if you can lead… plus other opportunities from other companies now that you’ve shown progress in this one!

It’s hard to go wrong having a blog, newsletter or podcast around something you’re interested in. Consider my post 32 reasons why you can’t afford not to start a podcast. It’s an easy way for people to find you, bring you opportunities… like Byron Dempsey getting involved with 18 & Lost.

How Does Tim Ferriss ‘Win Even If He Fails’

Ferriss always focuses on skills and relationships that will persist even after that project he’s trying, because you can’t ever know if it will ‘work out’ or ‘succeed’.

He discusses two examples — advising on an early company that didn’t work out, before later advising Uber. In this example, the skills were transferable.

Example number two is his book The 4 Hour Chef which didn’t go as well as he hoped with Amazon Publishing, but he developed a key relationship with HMH Books that later helped him. This is an example of a relationship he wouldn’t have developed if he stayed the course.

He discusses other skills — at the same time he was interviewed by people like Joe Rogan which gave him his first taste of podcasts. He soon after began The Tim Ferriss Show which as of now has more than seventy million downloads and impacts people globally. **

Takeaway

Figure out a way to protect the downside — learning and relationships are the best investments. They are easier to obtain than money and status, and they lead to money and status anyway. People have boosted my profile by interviewing me on podcasts, sharing my work, supporting me, helping me overcome fear and limiting beliefs — this comes through relationships.

I also enjoy these things no matter the results — for example in Constant Student I’m constantly connected with bright, talented and intentional people. Even if I didn’t make a dollar, even if I lost money, what an investment! You can’t place a dollar value on these relationships and learnings when you think long-term.

My work has already landed me investments in other companies, awareness of big future opportunities and a five figure consulting contract on the side! Plus I could get work out of these relationships in future, or collaborate with them on something new.

The flipside of protecting the downside is called upside stacking. Read more about that here.

‘Aim for the moon — if you miss you will hit the stars’. Open a Door, you will find more Doors you didn’t anticipate, you don’t need your original goal to be realised.

How Tim Ferriss Created His Own MBA

Ferriss went through the prospect of business school at Stanford but found a lot of abstract and theory-heavy classes. After conversations with a friend who was an investor, he thought ‘hang on, why don’t I take the money I would have spent on business school, (which was a whopping $120,000 at the time) and just invest that money myself and make my own real-world MBA?’

He created ‘the Tim Ferriss Fund’ and assumed he would lose the money over the two years, but figured the skills he’d learn and the people he’d meet would exceed in value the $120,000.

He lost $50,000 on the first investment! In saying that Ferriss went on to have a prolific investing career being early in companies like Shopify, Twitter, Uber and many, many more, so the experience was net positive. It is probably way more productive than going to do a traditional MBA and learn about things only in theory.

I have always followed a similar philosophy myself. My first proper business was Sydney Listings, a real estate agency, and I began it when I was twenty-two. The opportunity was presented to me and I knew I didn’t want to go back to university where you had to do tests and assignments and wait and wait before you could take action and have an impact.

So I figured, even if I don’t ‘make it’ or make a whole lot of money on this venture, I backed myself to learn so much that this would be a true degree — ultimately I would succeed even if I failed. Though the business was not a total failure, it definitely did not live up to my aspirations for it, commercially speaking. But I learnt so much about things as diverse as marketing, people, hiring, firing, handling risk, assessing the purchase of a business, financial management of a company, investing, property as an asset class, mortgages and much, much more… that’s not to include even the people and contacts I made.

So why isn’t everyone doing this? Well, it’s still scary to do this. Going to college or university, paying for course after course online is easier than actually stepping into the arena. Even though you agree you’ll learn more, there’s still a lot of fear. Don’t worry! Just keep reading.

Define Your Fears, Not Your Goals

This was the focus of Tim Ferriss’ TED Talk.

It goes through planning his suicide. He survived thanks to chance, but was interested in managing his ups and downs — Ferriss has bipolar depression.

The tool he’s found for emotional free-fall protection is ‘stoicism’ (here it is once again). He draws on examples like the upper ranks of the NFL and founding fathers like George Washington in terms of people who utilised stoic philosophy. He calls it an operating system for thriving in high pressure environments.

In 2004 he had a friend who died of pancreatic cancer, and his girlfriend left him when he was on the hustle hamster wheel, addicted to work. One day he read a quote by Seneca the Younger, ‘we suffer more often in imagination than in reality’, and decided to do something about it.

Premeditatio malorum

This means the pre-meditation of evils — imagining evils or scary situations beforehand so you can go through them. After reflecting on this, Ferriss created fear setting to help him take action. How does it work?

First there’s three columns… ‘DEFINE, PREVENT, REPAIR’, and you go through them for something you’re worried about.

Chances are — less intelligent and less driven people have figured these things out in the past. For example he was afraid of taking his first vacation in four years, worried about small things like missing a key letter from the IRS and having his business shut down.

So the PREVENT is to find an easy way to avoid that, like getting post sent to his accountant’s address.

The REPAIR column is for strategies to repair the situation even if the worst case scenario were to eventuate.

Then there is a second page, and that second page has the question ‘what might be the benefits of an attempt or partial success?’, something like increased confidence or skill progression. Here we’re very tentatively playing up the upside.

The final page is ‘THE COST OF INACTION’ and unpacks the risk of the status quo six months from now, a year from now and several years from now. Ferriss does this because we’re much more sensitive to pain than we are to pleasure or aspiration — we are more easily motivated to avoid things rather than move towards things.

For example, starting a project of some form and taking a ‘risk’ (I use the word in the traditional sense), what will be the risk in the future? Not having progressed and learnt, developed key skills, not having found the lifelong collaborators you’re meant to meet, and instead being stuck watching others take on daring and bold challenges and leading while you sit on the sidelines wondering what might have been.

Easy choices, hard life. Hard choices, easy life — Jerzy Gergorek

Ferriss ends his TED Talk by emphasising once again, ‘where in your life might defining your fears be more important than defining your goals’.

Great you can overcome fear… but the next question is, where’s your incentive to take action now?

Don’t forget, to get a summary of all writings and the podcast in five short bullet points each week, subscribe to The Doorman.

How to add a Sense of Urgency

Ferriss is a big fan of stoicism, like his friend Ryan Holiday.

He spends a lot of time meditating on death, as this gives a sense of urgency and forces him to have uncomfortable conversations that can change things.

When you push things like death out of focus, it’s too easy to avoid uncomfortable (but necessary) actions. He has a memento mori coin from Ryan Holiday and quotes that are etched on driftwood around his house to help him focus.

On death…

A — it’s outside your control. B — it happens to everyone, and C — you can hone your perception of death and make it more than an overwhelming sadness.

‘A wise sage once said, what are you unwilling to feel?’

For him, given his history with depression, he optimised everything to be positive and tried to cap any down moments. ‘But what you resist tends to persist’ which has a negative impact on your life.

One example for him is minor key music which has a note of melancholy — and he listened to it before something with a more upbeat track, to help him realise that the sadness is transient, that one’s psyche is porous. It flows in and then out, just like excitement.

Ferriss says — when you realise you can turn it on and turn it off, it loses its power over you. The problem is not death itself but the emotions you feel towards it.

Successful despite

“Successful people — however they define that — succeed despite their flaws, not because they don’t have any,”

“They succeed despite their insecurities, not because they don’t have any.”

The good thing about Tim Ferriss is that he admits that he has his moments — he has regularly seen a therapist, has snoozed in the morning, and often fritters away time.

This is a powerful cultural problem. People see something a celebrity or public figure has done and use that as a justification for unhealthy habits and behaviours.

A personal example for me was a friend who said you have to be a bit of a tyrant in business, have to be brutal and not enjoy it using an example like Steve Jobs. I pointed out that this logic was full of holes.

Steve Jobs is known for being abrasive around employees and team members. Does that mean you have to be abrasive to be ‘successful’? Of course not! What a ludicrous thought. And what’s more, what is successful, and can any man who has mistreated others be considered successful?